“Kabayan is mystical,” our guide Vince Gapuz says, “because there are many things about it that we have not been able to explain.”

My two travel buddies, Vince, and I are perched at the back of a small, four-by-four jeep. Its top has been removed to allow us to ogle the fantastic mountains surrounding our trip to Mount Timbac.

We hang on to the jeep’s bars and sides as it climbs through the dirt road. The ride is bumpy, rougher than the tricycle trip going to the junction of Batad. But the cool mountain air, glistening pine trees, and rice terraces are worth the dislocated joints I feel coming anytime now.

Vince made that comment in answer to our numerous questions about his hometown. Kabayan, a municipality in the eastern side of Benguet province, is the cultural center of his people–the Ibalois. Of the three indigenous tribes in Benguet, the Ibalois are said to be the only ones to practice mummification.

This is why my friends and I do not mind getting tossed and banged by this grumbling machine. In two hours, we will see the fire mummies of the Cordillera.

Tinongchol Burial Rock

But first, a stopover.

About 20 minutes into our trip, we get down in Barangay Kabayan Barrio and walk away from the road. Then, a hanging bridge, aglow in the morning light, greets us.

The bridge leads to Tinongchol Burial Rock, a huge boulder into which the Ibalois carved out openings and laid their dead to rest.

Making the holes and spaces in the rock was not easy. Vince says no iron tools were found inside when the tomb was discovered. The Ibalois drenched the rock with a ginger solution that softened the stone and made digging easier.

Coffins molded from pine trees peek out from the two openings we can see. Sadly, there are writings on some of them, the kind made by permanent marking pens. Even the isolation and height of the rock passages did not deter people from vandalizing the sacred spot.

I say a little prayer before I join the others back to the jeep. It is incoherent, but it must be my metaphorical way of doing the mano, the Filipinos’ traditional manner of showing respect to the elders.

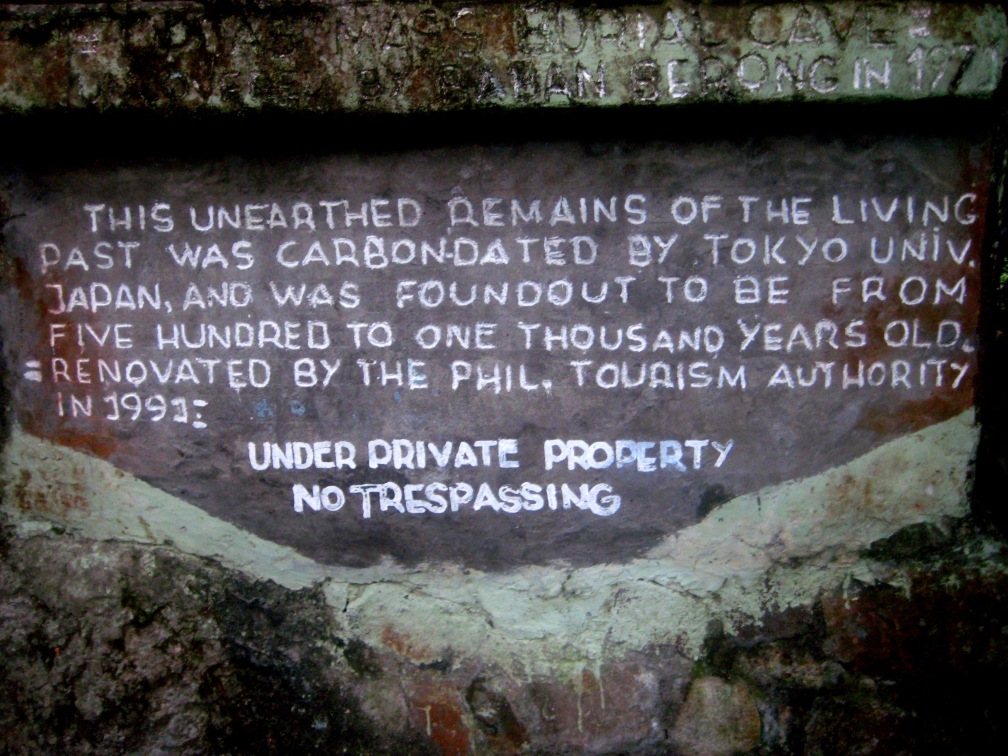

Opdas Mass Burial Cave

I pictured the same gesture in my head yesterday when we entered the Opdas Cave shortly upon arriving in Kabayan’s Poblacion or town center. Renovated into concrete, the cave has a gate and visitors need to ask for the key from the landowners.

Opdas Cave contains over 100 skulls and bones piled neatly inside. A pine coffin occupies the first row.

Who were they? And why were they all found in a mass grave?

Kenneth Kelcho, a resident who is working to preserve Kabayan’s rich culture, explained over native Cordillera coffee that no one knows the exact answers to these questions. One theory says they were the victims of an epidemic–perhaps cholera, the Spanish flu, or Hansen’s Disease–that swept through Kabayan about a century ago.

Today’s Ibalois do not know for sure if they are related to those interred in the Opdas Cave. Kenneth said they are waiting for word from a Japanese university that took DNA samples for testing. The results can help put to rest one of Kabayan’s mysteries and shed light to what can be an important part of its history.

Mt. Timbac’s Fire Mummies

After surviving the rough four-by-four ride, we come to Sitio Timbac, about 2,500 meters above sea level. We sit for a while on chopped pine trees used by resident Manang Loleng for firewood.

The air is still cold, but the sun shines clear through the mountaintops. I gaze at Mt. Pulag’s peak, the highest in Luzon, and at Agno River, the island’s third largest. It’s a good spot to soak in the silence and forget the world.

To see the mummies, we first walk about 100 steps down to more gorgeous views of the mountainside. I wish myself luck for the walk going back.

Along the path, Vince stops at an outcrop of rock similar but smaller to Tinongchol’s. He crouches and opens the rectangular gate at the bottom of the boulder. “One at a time,” he says. He crawls in, and my friend follows with her headlight.

Waiting for my turn, I can’t help but feel I’m violating something just by being here. It somehow doesn’t matter that viewing the mummies provides a link to my ancestors as a Filipino, even if I am not an Ibaloi. The thought of disturbing the resting place of people who once lived and mattered to others just to satisfy my curiosity doesn’t seem right. I feel a little bit appeased at having Vince, a true Ibaloi, guiding us. I whisper that prayer and imagine the gesture of respect as I ease into the cave.

There are eight pine coffins in the small space; two are opened for viewing. One contains a mother who Vince says died while giving birth. There is a hole in her womb from which the baby was taken out. Her organs, dry and withered but still well preserved, can be seen through the opening.

The other coffin contains a family–a child, two women, and what appears to be the father, a warrior in his time as shown by the intricate tattoos on his arms. How the patterns are preserved to this day is most extraordinary for me, as with the carvings on the coffin’s lid. I forget my uneasiness for a moment to marvel at all that detail.

Details that I decide not to photograph. I will contradict myself, more so as I described the mummies anyway, but I thought I should follow the sign inside the tomb.

To mummify their dead, Vince explains that the Ibalois used fire and blew smoke into the body’s openings to drain the fluids. They poured a salt solution through the mouth and repeatedly applied herbal juice such as from guava to the skin. They also placed the body under the sun to speed up the drying process that took up to two years. Then, the Ibalois transported the mummy and the coffin parts up to the rock caves. Here, they assembled the coffin and laid the mummy to rest. The cost it took to mummify the dead confined this practice to the rich.

Vince says Kabayan tried to recreate the process in the 1990s, but failed. As with most things in the town, it is uncertain why it did. Even the exact mummification process is unknown. Elders give different accounts.

As we leave Mt. Timbac through the Halsema Highway, I can’t help but regret how much of Kabayan’s history is still indefinite and undocumented.

On the other hand, there is something good in letting the mysteries of the town remain, for in trying to uncover them, we might inadvertently destroy the Ibaloi’s cultural treasures. Perhaps some things should remain a mystery.

_______________________________________

If you need a guide in Kabayan, contact Vince Gapuz at 0919-8524410.

there are lots of beauty to be defined, when we ‘re talking about Kabayan the mummius in the museum that has still tattos on there hands. i’ve seen that and the ‘eddet’ river. but the priceless to be discovered is the true behaviors of the ibaloi tribe cause once i’ve experienced it. more than words….. thanks kabayan …james

LikeLike

I like the presentation, short but precise…the pictures are adorable! Fantastic! Wonderful!

LikeLike

Thank you, Thelma 🙂

LikeLike

great. very educational. pls come back you still have many things to see. kudos

LikeLike

Thank you, Kuya Kenneth!:) We will definitely come back. I’m hoping to do the trek to Mt. Timbac when I’m more fit. Hehe. All the best!

LikeLike

nice story…….!!!! (^ ^)

LikeLike

Salamat, Vince! Bida ka diyan 😉

LikeLike